Dolley Madison became a legendary heroine in the 19th century and for much of the 20th. Not only were there biographies, but collections depicting the lives of great America women included her as a matter of course. By the end of the 19th century she had become useful to advertisers and thus was transformed into a mass marketing icon whose name lent cachet to a whole range of items. Indeed, her popular culture aura - and usefulness - transcended that of her husband. In this regard Dolley Madison is unique among women of the "colonial period" - a period loosely defined in terms of "colonial revival" as before 1840, or before modernization and industrialization seriously began in the United States. Dolley Madison became a legendary heroine in the 19th century and for much of the 20th. Not only were there biographies, but collections depicting the lives of great America women included her as a matter of course. By the end of the 19th century she had become useful to advertisers and thus was transformed into a mass marketing icon whose name lent cachet to a whole range of items. Indeed, her popular culture aura - and usefulness - transcended that of her husband. In this regard Dolley Madison is unique among women of the "colonial period" - a period loosely defined in terms of "colonial revival" as before 1840, or before modernization and industrialization seriously began in the United States.

The only other woman - and the only other First Lady - to became a popular culture symbol during the late 19th and 20th centuries is Martha Washington. But unlike Dolley Madison, Martha Washington was often paired with her husband. There are George and Martha salt and pepper shakers , George and Martha berry spoons, and George and Martha night lights. By contrast there are few popular culture artifacts that display Dolley and James together - indeed, there are few of James Madison at all. Dolley Madison almost always stands by herself, and is thus unique among "colonial" women.

The only other woman - and the only other First Lady - to became a popular culture symbol during the late 19th and 20th centuries is Martha Washington. But unlike Dolley Madison, Martha Washington was often paired with her husband. There are George and Martha salt and pepper shakers , George and Martha berry spoons, and George and Martha night lights. By contrast there are few popular culture artifacts that display Dolley and James together - indeed, there are few of James Madison at all. Dolley Madison almost always stands by herself, and is thus unique among "colonial" women.

This transformation of Dolley Madison into a popular culture image began in the late 19th century with "the colonial revival," a movement usually dated as beginning with the Philadelphia centenary celebration of 1876. By the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago a number of states had decided to build their state pavilions in the style of the Colonial Revival. By 1909 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City mounted the first serious exhibit of "colonial furniture" and by World War I new government housing for war workers was erected in that style. Today we live in a world suffused with colonial images, from our houses to our gas stations, post offices, churches, and shopping centers. We sit on colonial-style chairs, eat off of colonial-style dishes and use colonial-style flatware. There has, in this sense, never been an "end" to the revival; instead it has become deeply imbedded in our national identity. The use of Dolley Madison patterns and images on plates and for dolls, on fabrics, and for foods was part of that larger movement. This transformation of Dolley Madison into a popular culture image began in the late 19th century with "the colonial revival," a movement usually dated as beginning with the Philadelphia centenary celebration of 1876. By the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago a number of states had decided to build their state pavilions in the style of the Colonial Revival. By 1909 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City mounted the first serious exhibit of "colonial furniture" and by World War I new government housing for war workers was erected in that style. Today we live in a world suffused with colonial images, from our houses to our gas stations, post offices, churches, and shopping centers. We sit on colonial-style chairs, eat off of colonial-style dishes and use colonial-style flatware. There has, in this sense, never been an "end" to the revival; instead it has become deeply imbedded in our national identity. The use of Dolley Madison patterns and images on plates and for dolls, on fabrics, and for foods was part of that larger movement.

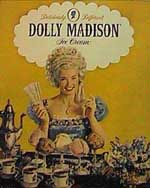

The colonial revival movement is very large and complex and as such it conveys no single meaning; nor does it depend upon what the actual historic figures, or their possessions, really looked like. It is the myth of American identity that is important here: what constitutes our central national experience; what was our golden age; and who we would like to be as a people? Colonial revivalism, moreover, produced artifacts that the rich could buy, the middle class could imitate, and the poor could have a piece of. Between the 1890s and the 1960s, after which the movement waned, not only did colonial styles of furniture and houses proliferate - defining where we sat and what we saw - but the advertising industry found colonial references a useful sales tool. Companies chose names that linked them with the golden era of the founders, including the Dolly Madison Ice Cream Company, the Dolly Madison Dairy Company and the Dolly Madison Bakery Company. Shoe manufacturers sold Dolly Madison styles and advertised their product with a Dolly Madison shoe hook. Chinaware companies created Dolly Madison dish patterns - as did flatware companies and glassware companies. The kitchen became an important corner of the colonial revival. Foodways were folkways that carried cultural messages. And perhaps most important, women had become important national consumers.

The colonial revival movement is very large and complex and as such it conveys no single meaning; nor does it depend upon what the actual historic figures, or their possessions, really looked like. It is the myth of American identity that is important here: what constitutes our central national experience; what was our golden age; and who we would like to be as a people? Colonial revivalism, moreover, produced artifacts that the rich could buy, the middle class could imitate, and the poor could have a piece of. Between the 1890s and the 1960s, after which the movement waned, not only did colonial styles of furniture and houses proliferate - defining where we sat and what we saw - but the advertising industry found colonial references a useful sales tool. Companies chose names that linked them with the golden era of the founders, including the Dolly Madison Ice Cream Company, the Dolly Madison Dairy Company and the Dolly Madison Bakery Company. Shoe manufacturers sold Dolly Madison styles and advertised their product with a Dolly Madison shoe hook. Chinaware companies created Dolly Madison dish patterns - as did flatware companies and glassware companies. The kitchen became an important corner of the colonial revival. Foodways were folkways that carried cultural messages. And perhaps most important, women had become important national consumers.

The colonial revival was a response to many changes in American society, including modernization, nationalism, industrialization, and immigration. "Colonial," moreover, meant many things to different people. For some it meant a golden era characterized by the virtues of honesty, sincerity and strength. For others it conveyed a return to an era before the corruption of large cities, immigrant politicians, and post-Civil War industrialism. For yet others it was a way to avoid the more "masculine" styles of Gothic and Craftsmen, and later of the machine age-inspired Art Deco. Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, an organization itself founded in the 1890s, became involved in preservation and interior design and wrote books on colonial dames and heroes as part of a way to preserve their heritage against the onslaught of the new immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. For immigrants and their children the style of Colonial Revival became one key to acculturation: if an object was manufactured in that style then it was genuinely "American" - and thus would help remake the immigrant's environment into one more in tune with American "culture." Still others found in the style a simplicity, an environment without pretension or claim to an aristocratic European past. By World War I, objects made in a colonial style could be labeled "made in America," and were patriotic. The strength and durability of the colonial revival lay in this multiplicity of definitions and uses.

Accordingly, the editors of the Dolley Madison Project have found dolls and china and silverware and cigarette advertisements identified with Dolley Madison. By the 1920s Dolley Madison had become a name through which to merchandise a whole series of artifacts, ranging from food to shoes and from jewelry to tobacco products. Her name had become an imprimatur.

Accordingly, the editors of the Dolley Madison Project have found dolls and china and silverware and cigarette advertisements identified with Dolley Madison. By the 1920s Dolley Madison had become a name through which to merchandise a whole series of artifacts, ranging from food to shoes and from jewelry to tobacco products. Her name had become an imprimatur.

No scholar has yet written about Dolley Madison as a figure in American popular culture, and the editors of this project have just begun collecting the images you will find in this section of our website. As part of that process we would like to encourage any of our readers who have a Dolley Madison popular culture artifact at home to send us a digital image. We are, moreover, open to any questions or thoughts or suggestions on this topic. But we can make a few educated guesses abut the meaning of the use of Dolley Madison in popular culture.

The Popular Culture Dolley Madison was a symbol of the changing American home. A famous hostess, she became an emblem of the social matron for the nation - and a suggestion that any woman could entertain as did Dolley Madison. There were foods associated with her name such as cakes, ice cream, milk, and popcorn. She was the domestic nurturer whose practices would insure wholesomeness and lend style to the contemporary mother. She was the brave guardian of the home - the American heroine who had stood up to the British in the War of 1812, saved the portrait of George Washington - and according to some legends even protected the Declaration of Independence from our enemies. She was a woman of beauty and fashion known for her turbans and dresses. Thus advertisers used her image to sell watches and nylon stockings, powder and rouge. She cared about her house décor. Dolley Madison furnished the White House, she was the lady of the house as designer and consumer.

The Popular Culture Dolley Madison was a symbol of the changing American home. A famous hostess, she became an emblem of the social matron for the nation - and a suggestion that any woman could entertain as did Dolley Madison. There were foods associated with her name such as cakes, ice cream, milk, and popcorn. She was the domestic nurturer whose practices would insure wholesomeness and lend style to the contemporary mother. She was the brave guardian of the home - the American heroine who had stood up to the British in the War of 1812, saved the portrait of George Washington - and according to some legends even protected the Declaration of Independence from our enemies. She was a woman of beauty and fashion known for her turbans and dresses. Thus advertisers used her image to sell watches and nylon stockings, powder and rouge. She cared about her house décor. Dolley Madison furnished the White House, she was the lady of the house as designer and consumer.

While she was the social matron for the nation, her image in popular culture helped domesticate, and thus tame, the emerging political power of women. The influence of a first lady provoked anxiety and threatened the status quo. This explains, at least in part, the negative reactions evidenced by some Americans to such twentieth century first ladies as Eleanor Roosevelt and Hilary Clinton. The power of the president's wife, who could exert influence through her personal connections, manipulate the men around her, and wield power in the public sphere, generated a growing political disquiet. The first lady did not hold an elected position, but she occupied a post that was nevertheless important to the workings of the state. For much of the late 19th and twentieth centuries, the popular culture images of Dolley Madison helped contain and restrict that power.

The Dolley Madisons we see in these artifacts of popular culture thus envision her in the domestic realm; she is the purveyor of food, clothing, household, and personal items. In a bedspread advertisement she holds a spread to her chest, wearing the sort of white colonial-era cap we associate with Betsy Ross - the nation's patriotic seamstress who gave birth to the flag, our national emblem. There are no images from Dolley Madison's lifetime that portray her in this style of cap, but through the visual link to Betsy Ross, the ad invites us to join Dolly Madison in acquiring fabrics to decorate our houses, to "Dress up your bed with a Dolly Madison Bed Spread and see what a difference it makes in the room." Dolly Madison's face appeals to us from the label of a pickle jar. From the cover of a sheet music song she stands before her Virginia home, Montpelier. And in a 1944 Avon advertisement, where an imagined scene from the War of 1812 becomes the image of home front patriotism, we are told that American women could contribute to the war effort -- and still remain feminine.

Our collection consists not only of categories of objects, but the ways in which they have changed over time. There is not only the beginning of this phenomenon, but its mutation and, at least for Dolley Madison - if not for Colonial Revivalism more generally - its end. With the exception of stamps and coins recently issued by the federal government, the prominence of Dolley Madison in popular culture - and her usefulness to the merchants of consumer America - died with the civil rights movement, the women's revolution, and cultural diversity. Our current image of her is now created by her "Colonial Era" portrait: a southern woman and a slave owner whose importance is now seen as largely derived from her husband's position rather than from her own efforts and who is thus currently viewed as performing wifely duties rather than thinking trenchant thoughts or performing independent deeds. In fact, the Dolley Madison we have brought to life through the rest of this website is a far more complex and interesting woman than her "colonial revival" image conveys. But that is the story of the rest of our website - and of our companion book.

The interested viewer may want to look at some of the more recent advertising artifacts produced by the Dolly Madison Bakery Company as a case study in reshaping the image of a company without changing its name. The Dolly Madison Bakery entered into a promotional contract with Charles Schultz that allowed the company to use the characters from "Peanuts" on a host of advertising gimmicks including, for example, drinking glasses and balloons. They changed their company logo to a generic woman who looks nothing like a colonial mistress. They produced advertisements featuring the rather anomalous combination of "Dolly Madison Bakery" packages with a Peanuts character on top of the First Lady's name: a dancing Snoopy, a Snoopy as the Red Baron, and so forth. Their new advertising doll became a young girl whose image is closer to Raggedy Ann than Dolley Madison. It is a testament to our changing times. Queen Dolley is no longer a saleable image.

The interested viewer may want to look at some of the more recent advertising artifacts produced by the Dolly Madison Bakery Company as a case study in reshaping the image of a company without changing its name. The Dolly Madison Bakery entered into a promotional contract with Charles Schultz that allowed the company to use the characters from "Peanuts" on a host of advertising gimmicks including, for example, drinking glasses and balloons. They changed their company logo to a generic woman who looks nothing like a colonial mistress. They produced advertisements featuring the rather anomalous combination of "Dolly Madison Bakery" packages with a Peanuts character on top of the First Lady's name: a dancing Snoopy, a Snoopy as the Red Baron, and so forth. Their new advertising doll became a young girl whose image is closer to Raggedy Ann than Dolley Madison. It is a testament to our changing times. Queen Dolley is no longer a saleable image.

We are still working on our collection and pondering our "finds", but in the process we are having a great time discovering all the Dolley Madison kitsch still in existence. It's fun! We hope that you enjoy this section of our website as much as we do.

For those interested in further reading we suggest:

Axelrod, Alan, ed. The Colonial Revival in America. (1985) Marling, Karal Ann. George Washington Slept Here: Colonial Revivals and American Culture, 1876-1986. (1988) Rhoads, William B. The Colonial Revival. (1977)

|