| Virginia Party Politics |

| Virginia Party Politics |

In the 1890's, the Republican Party of Virginia faced considerable

challenges.

The Walton Act helped to keep political

control in the hands of the Democratic party, by discouraging many

Republican and African American voters from visiting the polls. Democrats

also tried to

alienate Republicans from white voters by stigmatizing them as the "party

of the Negro." On November 9, 1898, The Daily Progress commented on

the effects of

Virginia's one-party system on the 1898 election results, in "A Quiet Day Everywhere and a Small

Vote." The election was marked by voter apathy.

|

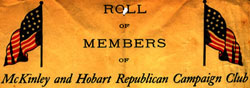

In an attempt to regain voter support, the Republican party urged local voters to form campaigning clubs in their ward or precinct. |

|

| Charlottesville's African Americans also participated in this Republican organizational drive. |  |

Despite continual African-American support, the Republican party

increased efforts to recover white votes through a "lily white" movement.

The Republican party proclaimed that it was a white man's party and had

no room to accomodate African Americans. In "WILL IT WORK," published August 13,

1900, The Daily

Progress questioned the feasibility and fairness of excluding African

Americans from the Republican Party.

During this period,

J.H. Rives, M.L. Price, and other Republican leaders wrote

letters expressing "lily white" sentiments and frustrations towards the

Democratic party which relentlessly continued to play the race card

against the Republican party.

The African-American Republican leaders felt the full

effects of the

"lily white" movement when they, along with their delegation, were barred

from the Republican Congressional Convention held at Luray in July,

1922.

Charlottesville sent two delegations to this convention. One, led by

R.N. Flannagan (President of the Henry Anderson Independent Club), was

all white. The other, led by City Chairman L.W. Cox, included

four African Americans. The convention decided to dismiss the Cox

delegation and seat the "lily-white" faction of Charlottesville's

Republicans. For more details see:

Charlottesville's African Americans had

been very active in Republican party politics at the turn of the

century.

Meeting accounts from April 10,

April 14, April

20, 1896 and June 18, 1901 report

extensive participation

by local African Americans such as Charles

E. Coles, George P.

Inge and J.T.S. Taylor.

The "Lily White" Movement: A Republican Party response to being

labled "the Party of the Negro"

An African-American Response Against Disfranchisement and Republican

Party exclusion

| Inge also co-signed this 1901 flyer during his service as local Republican Committee Chairman. |

|

A state-wide African-American movement protesting the disfranchisement of the 1901-1902 Constitutional Convention began in Charlottesville. On August 22, 1900, 100 African-American men from all over the state formed the Virginia Conference of Colored Men and met at the Odd Fellows' Hall "to petition against the proposed disfranchisement of the colored men of the state. The collection of African-American delegates included politicians, professors, lawyers, and reverends. The Daily Progress reported about the conference on August 20, August 22, and August 23, 1900.

The Conference of Colored Men later developed into the Virginia Educational and Industrial Association, sometimes referred to as the Negro Educational and Industrial Association. The organization met the following year in Staunton and next in Richmond, in 1902.

| A flyer surviving from 1901 suggests that, besides annual meetings, smaller local meetings were also being held. |

| Perhaps there were local branches of the association with individual agendas. |

By the 1902 annual meeting, the purpose of the Virginia (or Negro) Educational and Industrial Association was to raise funds to test the legality of the new Constitution. African-American lawyer James H. Hayes from Richmond and white attorney John S. Wise from New York led the court battles. On November 14, 1902, Jones et al. v. Montague et al., seeking a writ of prohibition, and Selden et al. v. Montague et al., seeking a writ of injunction were filed in the United States Circuit Court at Richmond. The prosecution raised charges that Governor Montague, members of the registration boards of election, and 50 members of the Constitutional Convention had deprived African Americans of the right to vote and that registrars were descriminating against African-American registrants. Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court Melville W. Fuller heard the cases in Circuit Court and dismissed both suits on lack of jurisdiction. Wise and Hayes submitted an appeal to the United States Supreme Court, but the previous decision was upheld in 1904.

Charlottesville African Americans remain persistent, however. In May 1907, The Daily Progress noted in "SWELLED CITY'S VOTING LIST" how the number of African-American registrants more than doubled in the past year.

Despite obstacles and setbacks, many African Americans continued to fight against disfranchisement and maintain their right to vote.

| Timeline | Home |