Documents

Official Records | Newspaper Materials | Slaveholder Records | Literature and Narratives

Official Records - Virginia Laws 1700-1750

An act for the more effectuall apprehending an outlying negro who hath commited divers robberyes and offences, 1701

This law, passed in 1701, concerns a specific slave, Billy, who ran away and may have organized a group of accomplices to commit a number of crimes in James City and New Kent counties. The act promised one thousand pounds of tobacco to anyone who killed or captured Billy and made it a felony to aid him.

An act to prevent the clandestine transportation or carrying of persons in debt, servants, and slaves, out of this colony, 1705

The year 1705 saw a spate of legislation dealing with slaves and servants.

One act addressed fears that ship captains might be carrying slaves and servants out of the colony:

An act declaring the Negro, Mulatto, and Indian slaves within this dominion, to be real estate, 1705

Another law of 1705 defined all slaves in Virginia as property.

An act concerning servants and slaves

Also in 1705, the Assembly passed a major omnibus bill incorporating most of the legal restrictions on slaves up to that point.

Part of the above law required that African-Virginians traveling away from the plantation were required to carry a pass "be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no slave go armed with gun, sword, club, staff, or other weapon, nor go from off the plantation and seat of land where such slave shall be appointed to live, without a certificate of leave in writing, for so doing, from his or her master, mistress, or overseer: And if any slave shall be found offending herein, it shall be lawful for any person or persons to apprehend and deliver such slave to the next constable or head-borough, who is hereby enjoined and required, without further order or warrant, to give such slave twenty lashes on his or her bare back well laid on, and so send him or her home. . ." A number of ads reveal that runaways attempting to gain their freedom might forge a pass in order to proceed without arrest. A typical pass might look like this.

Will, whom owner Robert Ruffin freed in 1710 for informing about a slave conspiracy

In colonial Virginia, manumission, or a master's freeing of a slave, was possible, but required a special act of the Assembly, usually done in cases of slaves' performing some service, such as this case.

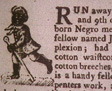

As the eighteenth century progressed, and the number of African-American slaves increased, the House of Burgesses enacted a number of laws specifically relating to runaway slaves. Rewards were set for capturing runaways; various officials, sheriffs, constables, justices, were empowered to deal with runaways or those suspected of running away; and procedures established for returning runaways.

An Act to make the Stealing of Slaves, Felony, without benefit of Clergy

In 1732 the House passed a law declaring it a felony without benefit of clergy to help a slave run away. The term benefit of clergy, applied in felony cases where the punishment was death, was a holdover from the Middle Ages that allowed criminals to escape the death sentence by proving that they could read and were thus clerics or priests. By the early eighteenth century, it was generally applied to all first-time felony cases in England. Its denial in this 1732 Virginia law is an indication of its relative severity.

An Act for settling some doubts and differences of opinion, in relation to the benefit of Clergy

At the same time, the Assembly noted for the first time that benefit of clergy also applied to slaves, except in cases of manslaughter, theft of goods valued at more than five pounds, or repeat offenders.

Series of Acts for the better Regulation of the Militia

In 1738 the Assembly passed one of a series of acts "for the better Regulation of the Militia." It stipulated that blacks, free and slave, and Indians could not bear arms, but could serve as "drummers, trumpeters, or pioneers, or in such other servile labour."

The Case of William Chamberlain

Occasionally the Assembly acted in cases of family disputes over the distribution of property. In the case of William Chamberlain, a merchant of New Kent County, his slaves were divided among his heirs after his death without provision for his unborn daughter. One of Chamberlain's sons, Edward Pie, at one time owned the notorious runaway Cambridge.

In October 1748, the Assembly enacted a number of laws designed to codify legislation since 1705 and provide tighter controls over runaways and slaves convicted of crimes.

An Act concerning Servants, and Slaves

This act, included, among other things, a lengthy set of provisions dealing with captured runaways. [For a jailer's advertisement referring to this act, see Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), August 15, 1766.]

An Act Concerning Tithables

This act provided that imported slaves were to be shown before the county court to have their ages certified. [See Richmond County court records for examples.]

An Act to prevent the clandestine transportation, or carrying of persons in debt, servants, or slaves, out of this Colony

An Act Directing the Trial of Slaves Committing Capital Crimes

This act set up special courts to try slaves for felonies, plots and conspiracies. Lawmakers singled out poisoning as a special fear.

An Act for making provision against Invasions and Insurrections

This act addressed the burgesses' fears of foreign invasions and slave revolts.

An Act against stealing Hogs

Finally, this act provided more severe punishments for slaves convicted of stealing hogs than those for whites.

|

![]()