![]()

![]()

A NEW COLLECTION OF VOYAGES, DISCOVERIES and TRAVELS:

CONTAINING Whatever is worthy of Notice, in EUROPE, ASIA, AFRICA and AMERICA IN RESPECT TO The Situation and Extent of Empires, Kingdoms, and Provinces; their Climates, Soil, Produce &c.

WITH The Manners and Customs of the several Inhabitants; their Government, Religion, Arts, Sciences, Manufactures, and Commerce

The whole consisting of such ENGLISH and FOREIGN Authors as are in most Esteem; including the Descriptions and Remarks of some celebrated late Travellers; not to be found in any other Collection. Illustrated with a Variety of accurate MAPS, PLANS, and elegant ENGRAVINGS.

VOL. VI.

LONDON:

Printed for J. KNOX, near Southampton-Street, in the Strand. MDCCLXVII.

TRAVELS Into the Inland Parts of AFRICA, BY FRANCIS MOORE.

I LEFT England, says Mr. Moore, in July 1730, on being appointed a writer in the service of the Royal African company, and on the 9th of November came to an anchor in the mouth of the Gambia. As we sailed up that river near the shore, the country appeared very beautiful, being for the most part woody; and between the woods were pleasant green rice grounds, which after the rice is cut, are stocked with cattle. On the 11th we landed at James's Island, which is situated in the middle of the river, that is here at least seven miles broad. This island lies about ten leagues from the river's mouth, and is about three quarters of a mile in circumference. Upon it is a square stone fort regularly built , with four bastions; and upon each are seven guns well mounted, that command the river all round: beside, under the walls of the fort facing the sea, are two round batteries, on each of which are four large cannon well mounted, that carry ball of 24 pounds weight, and between these are nine small guns mounted for salutes.

Beside the fort, there are several factories up the river, settled for the convenience of trade; but they are all under the direction of the governor and chief merchants of the fort. For this purpose the com

Soon after my arrival, I supped upon oysters that grew upon trees: this being somewhat remarkable, it may be thought worthy of an explanation. Down the river, where the water is salt, and near the sea, the river is bounded with trees called Mangroves; whose leaves being long and heavy, weigh the boughs into the water: to these leaves the young oysters fasten in great quantities, where they grow till they are very large, and then you cannot separate them from the tree, but are obliged to cut off the boughs with the oysters hanging on them, resembling ropes of onions.

On the 22d of February, one of the kings of Fonia came to the fort, and on his landing was saluted with five guns. He came to see the governor, or rather to ask for some powder and ball, in order to enable him to defend himself against some people with whom he was at war: he was a young man, very black, tall, and well set; was dressed in a pair of short yellow cotton-cloth breeches, and wore on his back a garment of the same cloth, made like a surplice: he had on his head a very large cap, to which was fastened part of a goat's tail, which is a customary ornament with the great men of this river; but he had no shoes nor stockings. He and his retinue came in a large canoe, holding about 16 people, all armed with guns and cutlasses. With him came two or three women, and the same number of Mundingo drums, which are about a yard long, and a foot or twenty inches diameter at the top, but less at the bottom; made out of a solid piece of wood, and covered at the widest end with the skin of a kid.

It may be here proper to observe, that there are many different kingdoms on the banks of the Gambia, inhabited by several races of people, as Mundingoes, Jolloiffs, Pholeys, Floops, and Portuguese. The most numerous are called Mundingoes, as is likewise the country they inhabit: these are generally of a black colour, and well set. When this country was conquered by the Portuguese, about the year 1420, some of that nation settled in it, who have cohabited with these Mundingoes, till they are now very near as black as they: but as they still retain a sort of bastard Portuguese language, called Creole, and as they christen and marry by the help of a priest annually sent thither from St. Jago, one of the Cape de verde islands, they still esteem themselves Portuguese Christians, as much as if they were actually natives of Portugal; and nothing angers them more than to call them Negroes, that being a term they use only for slaves.

On the north-side of the river Gambia, and from thence in-land, are a people called Jolloiffs, whose country extends even to the river Senegal. These people are much blacker, and handsomer than the Mundingoes; for they have not the broad nose and thick lips peculiar to the Mundingoes and Floops.

In every kingdom and country on each side of the river are people of a tawney colour, called Pholeys, who resemble the Arabs, whose language most of them speak; for it is taught in their schools; and the koran, which is also their law, is in that language. They are more generally learned in the Arabic, than the people of Europe are in Latin; for they can most of them speak it, though they have a vulgar tongue

In these countries the natives are not avaricious of lands; they desire no more than what they use, and as they do not plough with horses or cattle, they can use but very little.

The natives make no bread, but thicken liquids with the flour of the different grains. The maize they mostly use when green, parching it in the ear, when it eats like green peas. their rice they boil in the same manner as is practiced by the Turks; and make flour of the Guinea corn and mansaroke, as they also sometimes do of the two former species, by beating it in wooden mortars. The natives never bake cakes or bread for themselves, but those of their women who live among the Europeans learn to do both.

The Pholey are the greatest planters in the country, though they are strangers in it. They are very industrious and frugal, and raise much more corn and cotton than they consume, which they sell at reasonable rates; and are so remarkable for their hospitality, that the natives esteem it a blessing to have a Pholey town in the neighbourhood: beside, their behaviour has gained them such a reputation, that it is esteemed infamous for any one to treat them in an inhospitable manner.

The most general language used in these countries is the Mundingo; and whoever can speak it, may

The next language mostly used here is called the Creole Portuguese; though I believe it would be scarce understood at Lisbon: it is, however, sooner learnt by Englishmen, than any other language used on the banks of this river, and is always spoken by the linguists or interpreters; and these two I learnt whilst in the river.

The Arabic is not only spoken by the Pholeys, but by most of the Mahometans in the river, though they are Mundingoes; and it is observed, that those who can write that language are not only very strict at their devotions three or four times a day; but are remarkably sober and abstemious in their manner of living.

On the 4th of April I went to Gillyfree, which is a large town, a little below James's fort, inhabited by Portuguese, Mundingoes, and some Mahometans, who have here a pretty little mosque. The English company have a factory here, pleasantly situated, facing the fort, and also some gardens that supply the fort with greens and fruit.

A native here took me to his house, and shewed me a great number of arrows, daubed over with a black mixture, said to be so venomous, that if the arrow did but draw blood it would be mortal, unless the person who made the mixture had a mind to cure it; for the man observed, that there were no poisonous herbs, whose effects might not be prevented by the application of other herbs.

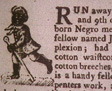

On the 11th, came down the river a vessel commanded by captain Pyke, a separate trader, from Joar, loaded with slaves, among whom was a person

On the 29th, the governor and I set out for Vintain, where we arrived in three hours, though it lies about six leagues from James's fort. On our coming to the town, the Alcade, and all the principal inhabitants came to welcome us; and soon after came the prince, in whose dominions the town is situated.

The inhabitants are not very curious in their furniture, for the most that any of them have is a small chest for cloaths, a matt raised upon posts from the ground, to lie on; a jar to hold water, a callabash to drink it with; two or three wooden mortars, in which they pound their corn and rice; a basket which they use as a sieve, and two or three large callabashes, out of which they eat with their hands instead of spoons. They are not very careful of laying up store against a time of scarcity; but chuse rather to sell what they can, as upon occasion they can fast two or three days without eating; but then they are always smoaking tobacco, which is of their own growth.

Here are cameleons, and great numbers of crocodiles, which the natives kill and eat: they admire

Whilst I was here, I saw an ostrich, with a man riding upon its back, who was going down to the fort; it being a present to the governor, from one of our factors, who bought it at Fatatenda.

Soon after my arrival at Joar, the king of Barsally came thither, attended by three of his brothers, above 100 horsemen, and as many foot; and though he had a house of his own in the town, he insisted on lying at the factory. Mr. Roberts, Mr. Harrison, who were factors, and I, were all the English there. the king immediately took possession of Mr. Roberts's bed; and then having drank brandy till he was drunk, ordered Mr. Roberts to be held, while he himself took out of his pocket the keys of the storehouse, into which he and several of his people went, and took what they pleased: he searched chiefly for brandy; of which there happened to be but one anchor: he took that, and having drank till he was dead drunk, was put to bed. This anchor lasted him three days; and it was no sooner empty, than he went all over the house to seek for more. At last he entered a room, in which Mr. Harrison lay sick, and seeing there a case that contained six gallons and a half, that belonged to him and me, he ordered Mr. Harrison to get out of bed and open it: he, however, told him with great gravity, that there was nothing in it but some of the company's papers; and that it must not be opened; but the king was too well acquainted with liquor cases to be so easily deceived; and therefore ordered some of his men to hold Mr. Harrison in bed, while he himself took the key out of his breeches pocket. He then opened the chest, took out all the liquor, and was not sober while it lasted: but he often sent for Mr. Harrison and me to drink with him. At length it being all drank, he

Sometimes the king would ride abroad, and take most of his attendants with him: but when he was gone we were plagued with the company of two of this brothers, who were, if possible, worse than his majesty. Once during his absence Boomey Haman Benda, one of these princes, laid hold of a mug of water, and pretending to drink, took a mouthful, and then setting the mug on the table, spurted the water in my face. Upon which, considering that if I suffered such insolence to pass unresented, it would render me liable to be continually insulted, I took the remainder of the water, and threw it into his breeches. Upon this he pulled out his knife, and endeavoured to stab me, but was prevented by his favorite attendant, who held his arm, and soon after represented to him the unhandsome manner in which he had treated me, and the provocation I had received to wet him. This made him so ashamed, that coming up to me, he laid himself down on the floor without his garment, took my foot, and placed it on his neck, and there lay till I desired him to rise: after which, no man appeared more my friend, no shewed greater willingness to oblige me.

This king, as well as all his attendants, are of the Mahometan religion, notwithstanding their being such drunkards; and this monster, when he is sober, even prays. His people, as well as himself, always wear white cloaths and white caps; and as they are exceeding black, this dress makes them look exceeding well.

This tyrant is tall, and so passionate, that when any of his men affront him, he makes no scruple of shoot

The dominions of this prince are very extensive, and are divided into several provinces, over which he appoints governors, called boomeys, who annually come to pay him homage.

At length the king and his guards, to our great joy, left the factory, in order to return to Cohone; but they first stript Mr. Roberts's chamber, and took away his cloaths and books, which last they offered to sell to a Mahometan priest; but he being a friend to Mr. Roberts, told them, he believed they were books in which he kept the account of his goods, and that to take them would inevitably ruin him: upon which they gave him leave to return them.

However, five months after, the king of Barsally paid us another visit, and staying about a week, during which he behaved much in the same manner as before, he and his attendants again left us; but some of them first broke open my bureau, and took out things to a considerable value; and the same fate attended Mr. Roberts: besides which they took a great quantity of the company's goods.

In the interval which passed between these two visits, I had been made factor, and had received orders to take charge of the factory of Joar: but I was unwilling to accept this office, as that factory was liable to many insults from a drunken monarch, void of every principle of justice, and destitute of the

In March I returned to my factory: but Mr. Hugh Hamilton being sent up the river to settle a factory at Fatatenda, I was permitted to accompany him; and accordingly on the 9th on the 9th of April we left Joar, and proceeded in a sloop up the Gambia. The next day we arrived at Yanimarew, which is the pleasantest port on the whole river, the country being delightfully shaded with palm and palmetto trees. The company have here a small house, with a black factor, to purchase corn for the use of the fort.

On my arrival at Nackway, the natives welcomed me with the music of the balafeu, which, at about 100 yards distance, sounds something like a small organ. It is composed of about 20 pipes of very hard wood finely polished; which diminish by little and little, both in length and breadth, and are tied together by thongs of very fine leather. These thongs are twisted about small round wands, put between the pipes to keep them at a distance; and underneath the pipes are fastened 12 or 14 callabashes of different sizes. This instrument they play upon with two sticks, covered with a tin skin taken from the trunk of the palmetto tree, or with fine leather, to make the sound less harsh. Both men and women dance to this music, which they much admire, and are highly delighted to have a white man dance with them.

Having finished my business here, I returned to Yamyamacunda; and having continued there about three months, proceeded still farther up the river to Fatatenda. The Gambia is there as wide as the Thames at London-Bridge, and seemed very deep; but what is most extraordinary, the tide in the dry season rises three or four feet, though that place is 600 miles from the river's mouth.

I stayed at Yamyamacunda, till the 5th of May, 1734; and was employed in the company's service in different parts of the river till the 13th of July following, when I was desired to come down to James's Fort: I was there on the 8th of August, when the Dolphin snow arrived, with four writers, and Job Ben Solomon, on board. We have already mentioned his being robbed and carried to Joar, where he was sold to captain Pyke, by whom he was carried to Maryland. Job was there sold to a planter, with whom he had lived about a twelvemonth, in all which time he had the happiness not to be struck by his master, and then the good fortune to have a letter of his own writing in the Arabic tongue conveyed to England. This letter coming to the hand of Mr. Oglethorp, he sent it to Oxford to be translated; which being done, it gave him such satisfaction, and inspired him with so good an opinion of the author, that he immediately sent orders to have him bought of his master. This happened a little before that gentleman's setting out for Georgia; and before his return from thence, Job arrived in England; where being brought to the acquaintance of Sir Hans Sloane, he was found to be a perfect master of the Arabic tongue, by his translating several manuscripts and inscriptions on medals. That learned antiquary recommended him to the duke of Montague, who being pleased with his genius and capacity, the agreeableness of his behaviour, and the sweetness of his temper, introduced him to court; where he was graciously received by the royal family and most of the nobility, who

On his arrival at James's Fort, Job desired that I would send a messenger to his country to let his friends know where he was. I spoke to one of the blacks whom he usually employed, to procure me a messenger, and he brought me a Pholey, who not only knew the high priest his father, but Job himself, and expressed great joy at seeing him safely returned from slavery; he being the only man, except one, ever known to come back to his country, after being once carried a slave out of it by white men. Job gave him the message himself, and desired that his father would not come down to him, observing that it was too far for him to travel; and that it was fit the young should go to the old, and not for the old to come to the young. He also sent some presents to his wives; and desired the man to bring his little one, who was his best beloved, down to him.

Job having a mind to go up to Joar, to talk with some of his countrymen, went along with me. We arrived at the creek of Damasensa; and having some old acquaintances at the town of that name, Job and I went in the yawl: in the way going up a narrow place for about half a mile, we saw several monkeys

In the evening as my friend Job and I were sitting under a great tree at Damasensa, there came six or seven of the very people, who, three years before, had robbed and made a slave of him, at about 30 miles distance from that place. Job, though naturally possessed of a very even temper, could not contain himself on seeing them: he was filled with rage and indignation, and was for attacking them with his broadsword and pistols, which he always took care to have about him. I had much ado to dissuade him from rushing upon them: but at length representing the ill consequences that would infallibly attend so rash an action, and the impossibility that either of us should escape alive, I made him lay aside the attempt, and persuading him to sit down, and pretending not to know them, to ask them questions about himself; which he accordingly did; and they told him the truth. At last he enquired how the king their master did? they replied that he was dead; and by farther inquiry we found that amongst the goods for which he sold Job to captain Pyke there was a pistol, which the king used commonly to wear slung by a string about his neck; and as they never carry arms without their being loaded, the pistol one day accidentally went off, and the balls lodging in his throat, he presently died. Job was so transported at the close of this story, that he immediately fell on his knees, and returned thanks to Mahomet for making him die by the very goods for which he sold him into slavery. The returning to me, he cried, "You see now, Mr. Moore, that God Almighty was displeased at this man's making me a slave, and therefore made him die by the very pistol for which he sold me: yet I ought to forgive him, because had not I been sold,

After this Job went frequently with me to Cower, and several other places about the country. He always spoke very handsomely of the English; and what he said removed much of that horror the Pholeys felt for the state of slavery amongst them. For they before generally imagined, that all who were sold for slaves, were at least murdered, if not eaten, since none ever returned. His descriptions also gave them a high opinion of the power of England, and a veneration for the English, who traded amongst them. He sold some of the presents he brought with him for trading goods, with which he bought a woman slave, and two horses, which he designed to take with him to Bundo. He gave his countrymen a good deal of writing paper, a very valuable commodity amongst them, for the company had made him a present of several reams. He used frequently to pray; and he behaved with great affability and mildness to all, which rendered him extreamly popular.

The messenger not returning so soon as was expected, Job desired to go down to James's Fort, to take care of his goods; and I promised not only to send him word when the messenger came back, but to send other messengers, for fear the first should have miscarried.

At length the messenger returned with several letters, and advice that Job's father was dead; but had lived to receive the letters his son had sent him from England, which gave him the welcome news of his being redeemed from slavery, and an account of the figure he made in England: that one of Job's wives

As I have brought this account almost to the time of my leaving this country, it will be necessary to give a more particular description of it, with respect to the climate, the general customs of the natives, and the trade carried on there.

As the mouth of the Gambia lies in the latitude of 130; 20' north, and 150; 20' west longitude, there is no wonder that the climate is excessive hot; but the greatest heats are generally about the latter end of May, a fortnight or three weeks before the rainy season begins. The sun is perpendicular twice in the year, and the days are never longer from sun-rising to sun-set than 13 hours, nor even shorter than 11. What at first seemed to me strange, was that as soon as it grew light, the sun arose, and it no sooner set than it grew dark.

The rainy season commonly begins with the month of June, and continues till the latter end of September, or the beginning of October. The wind comes first and blows excessive hard, for the space of half an hour or more, before any rain falls, so that a vessel

Four months in the year are unhealthful, and very tedious to those who come from a colder climate; but a perpetual spring, in which you commonly see ripe fruit and blossoms on the same tree, makes some amends for that inconvenience. Beside, the heat of the air is frequently moderated by pleasant and refreshing breezes.

The Gambia is of such a length as to be navigable for sloops above 600 miles, the tides reaching so far from its mouth. The land on each side of this great and fine river is for the most part flat and woody about a quarter of a mile beyond its banks: and within that space are pleasant open grounds, on which the natives plant rice; and in the dry season it serves the cattle for pasture. Thus within land it is generally very woody; but near the towns there is always a large spot of ground cleared for corn. near the sea no hills are to be seen; but high up the river are lofty

In every kingdom there are several persons called lords of the soil, who have the property of all the palm and palmetto trees, so that none are allowed to draw any wine from them, without their knowledge and consent. Those who obtain leave to draw wine, give two days produce in a week, to the lord of the soil; and white men are obliged to make a small present to them, before they cut palmetto leaves, or grass, to cover their houses.

The palm is a fine straight tree that grows to a prodigious height, and out of it the natives extract a sort of white liquor like whey, called palm wine; by making an incision on the top of the trunk, to which they apply gourd bottles, and into these the liquor runs by means of a pipe made of leaves. This wine is very pleasant as soon as it is drawn, it being extraordinary sweet; but is apt to purge very much: however, in a day or two it ferments, and grows rough and strong like Rhenish wine; when not being at all prejudicial to the health, it is plentifully drank by all the negroes. It is very surprising to see how nimbly the natives will go up these trees, which are sometimes 60, 70, or 100 feet high, and the bark smooth. They have nothing to help them to climb, but a piece of the bark of a tree made round like a hoop, with which they enclose themselves and the tree; then fixing it under their arms, they set their feet against the tree, and their backs against the hoop, and go up very fast: but sometimes they miss their footing; or the bark on which they rest breaks or comes untied, when falling down, they lose their lives.

The people here, as in all other hot countries, marry their daughters very young; even some are contracted as soon as they are born, and the parents can never after break the match; but it is in the power

When a man takes home his wife, he makes a feast at his own house, to which all who please come without the form of an invitation. The bride is brought thither upon mens shoulders, with a veil over her face, which she keeps on till she has been in bed with her husband, during which the people dance and sing, beat drums, and fire muskets.

After his wife is brought to bed, she is not to lie with her husband for three years, if the child lives so long; for during that term the child sucks, and they are firmly persuaded that lying with their husbands would spoil their milk, and render the child liable to many diseases. The women alone are subject to all the mortifications attending so long an abstinence; for every man is allowed to take as many wives as he pleases: but if the wife is found false to her husband, she is liable to be sold for a slave. Upon any dislike, a man may turn off his wife, and make her take all her children with her; but if he has a mind to take any of them himself, he generally chuses such as are big enough to assist him in providing for his family. He has even the liberty of coming several years after they have parted, and taking from her any of the children he had by her. But if a man is disposed to part with a wife who is pregnant, he cannot oblige her to go till she is delivered.

The women are kept in the greatest subjection; and the men, to render their power as compleat as possible, influence their wives to give them an unlimited obedience, by all the force of fear and terror. For this purpose the Mundingoes have a kind of image eight or nine feet high, made of the bark of

About the year 1727, the king of Jagra having a very inquisitive woman to his wife, was so weak as to disclose to her this secret; and she being a gossip, revealed it to some other women of her acquaintance. This at last coming to the ears of some who were no friends to the king, they, dreading lest if the affair took vent, it should put a period to the subjection of their wives, took the coat, put a man into it, and going to the king's town, sent for him out, and taxed him with it: when he not denying it, they sent for his wife, and killed them both on the spot. Thus the poor king died for his complaisance to his wife, and she for her curiosity.

The women pay such respect to their husbands, that when a man has been a day or two from home his

When a child is born they dip him over head and ears in cold water three or four times in a day; and as soon as he is dry, rub him over with palm oil, particularly the back-bone, the small of the back, the elbows, the neck, knees, and hips. When they are born they are of an olive colour, and sometimes do not turn black till they are a month or two old.

I do not find that they are here born with flat noses; but the mothers, when they wash the children, press down the upper part of the nose: for large breasts, thick lips, and broad nostrils, are esteemed extreamly beautiful. One breast is generally larger than the other.

About a month afterward they name the child, which is done by shaving its head, and rubbing it over with oil; and a short time before the rainy season, they circumcise a great number of boys, of about 12 or 14 years of age, after which the boys put on a peculiar habit; the dress of each kingdom being different. From the time of their circumcision to that of the rains, they are allowed to commit what outrages they please, without being called to account for them; and when the first rain falls, the term of this licentiousness being expired, they put on their proper habit. The people are naturally very jocose and merry, and will dance to a drum or ballafeu, sometimes 24 hours together, now and then dancing very regularly, and at other times using very odd gestures, striving always to outdo each other in nimbleness and activity.

The behaviour of the natives to strangers is really not so disagreeable as people are apt to imagine; for when I went through any of their towns, they almost all came to shake hands with me, except some of the women, who having never before seen a white man,

Some of the Mundingoes have many slaves in their houses; and in these they pride themselves. They live so well and easily, that it is sometimes difficult to know the slaves from their masters and mistresses; they being frequently better cloathed, especially the females, who have sometimes coral, amber, and silver, about their wrists, to the value of 20 or 30 l. sterling.

In almost every town they have a kind of drum of a very large size, called a tangtong, which they only beat at the approach of an enemy, or on some very extraordinary occasion, to call the inhabitants of the neighbouring towns to their assistance; and this in the nigh-time may be heard six or seven miles.

There was a custom in this country which is not thoroughly repealed, that whatever commodity a man sells in the morning, he may, if he repents his bargain, go and have it returned to him again, on his paying back the money any time before the setting of the sun the same day. This custom is still in force very high up the river; but below it is pretty well worn out.

Whenever any factories are settled, it is customary to put them, and the persons belonging to them, under the charge of the people of the nearest large town, who are obliged to take care of it, and to let none impose upon the white men, or use them ill; and if any body is abused, he must apply to the alcalde, the head man of the town, who will see that justice is done him. This man is, up the river, called the white man's king; and has beside very great power. Almost every town has two common fields,

The trade of the natives consists in gold, slaves, elephants teeth, and bees-wax. The gold is finer than sterling, and is brought in small bars, big in the middle, and turned round into rings, from 10 to 40 s. each. The merchants who bring this, and other inland commodities, are blacks of the Mundingo race, called Joncoes, who say, that the gold is not washed out of the sand, but dug out of mines in the mountains, the nearest of which is 20 days journey up the river. In the country where the mines are, they say there are houses built with stone, and covered with terras; and that the short cutlasses and knives of good steel, which they bring with them, are made there.

The same merchants bring down elephants teeth,and in some years slaves to the amount of 2000, most of whom they say are prisoners of war; and bought of the different princes by whom they are taken. The way of bringing them is, by tying them by the neck with leather thongs, at about a yard distance from each other, 30 or 40 in a string, having generally a bundle of corn, or an elephant's tooth upon each of their heads. In their way from the mountains they travel through extensive woods, where they cannot for some days get water; they therefore carry in skin bags enough to support them for that time. I cannot be certain of the number of merchants who carry on this trade; but there may perhaps be about 100 who go up into the inland country with the goods, which they buy from the white men, and with them purchase, in various countries, gold, slaves, and elephants

Beside the slaves brought down by the negro merchants, there are many bought along the river, who are either taken in war like the former, or condemned for crimes, or stolen by the people: but the company's servants never buy any which they suspect to be of the last sort, till they have sent for the alcalde, and consulted with him. Since this slave trade has been used, all punishments are changed into slavery; and the natives reaping advantage from such condemnations, they strain hard for crimes, in order to obtain the benefit of selling the criminal: hence not only murder, adultery, and theft, are here punished by selling the malefactor; but every trifling crime is also punished in the same manner. Thus at Cantore, a man seeing a tyger eating a deer, which he himself had killed and hung up near his house, fired at the tyger, but unhappily shot a man: when the king had not only the cruelty to condemn him for this accident; but had the injustice and inhumanity to order also his mother, his three brothers, and his three sisters, to be sold. They were brought down to me at Yamyamacunda, when it made my heart ache to see them; but on my refusing to make this cruel purchase, they were sent father down the river, and sold to some separate traders at Joar, and the vile avaricious king had the benefit of the goods for which they were sold.

Indeed the cruelty and villainy of some of these princes can scarcely be conceived. Thus, whenever the king of Barsally, some of whose villainies I have already mentioned, wants goods or brandy, he sends to the governor of James's Fort, to desire him to send a sloop there with a proper cargo; which is readily complied with. Mean while, the king goes and ransacks some of his enemies towns, and seizing the innocent people, sells them to the factors in the sloop

Several of the natives of these countries have many slaves born in their families. This there is a whole village near Brucoe of 200 people, who are the wives, slaves, and children of one man. And though in some parts of Africa they sell the slaves born in the family; yet this is here thought extreamly wicked; and I never heard but of one person who ever sold a family slave, except for such crimes as would have authorised its being done, had he been free. Indeed, if there are many slaves in the family, and one of them commits a crime, the master cannot sell him without the joint consent of the rest: for if he does, they will run away to the next kingdom, where they will find protection.

Ivory, or elephants teeth, is the next principal article of commerce. These are obtained either by hunting and killing the beasts, or are picked up in the woods. This is a trade used by all the nations hereabouts; for whoever kills an elephant, has the liberty of selling him and his teeth. But those traded for in this river are generally bought from a good way within the land. The largest tooth I ever saw weighed 130 pounds.

The fourth branch of trade consists in bees-wax. The Mundingoes make beehives of straw shaped like ours, and fixing to each a bottom board, in which is a hole, for the bees to go in and out, hang them on the boughs of trees. They smother the bees in order to take the combs, and pressing out the honey, of which they make a kind of metheglin, boil up the

At length, on the 8th of April 1735, having delivered up the company's effects to Mr. James Conner, I embarked on board the company's sloop. Among other persons, Job came down with me to the sloop, and parted with me with tears in his eyes; at the same time giving me letters to the duke of Montague, the royal African company, Mr. Oglethorpe, and several other gentlemen in England, telling me to give his love and duty to them, and to acquaint them, that as he designed to learn to write the English tongue, he would, when he was master of it, send them longer epistles. He desired me, that as I had lived with him almost ever since he came there, I would let his grace and the other gentlemen know what he had done; and that he was going to the gum forest, and would endeavour to produce so good an understanding between the company and the Pholeys, that he did not doubt but that the English would procure the gum trade: adding, that he would spend his days in endeavouring to do good to the English, by whom he had been redeemed from slavery, and from whom he had received innumerable favours.

Soon after he returned on shore, while I sailed to England; and at length, on the 13th of July, landed at Deal.

Bibliographic Information

Availability

Available to the general public at URL: /gos/

Text and images © copyright 2003, by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia